The NASA Years

1987 - 2007

My NASA years, beginning in 1987 and continuing until my retirement and transition to Stanford in 2007, represent the pinnacle of my accomplishments in space exploration. In order to make sense of all the pages of my detailed oral history conducted for the NASA Headquarters Science Mission Directorate Oral History Project, as well as the detailed entries in my CV, it is necessary to know a bit about the Agency’s management structure.

Over my 20 years, I went back and forth between line management and project/program management.

In line management one is primarily responsible as a supervisor for people and for the project or research they undertake. A Branch Chief or Division Chief is responsible for recruiting, mentoring and assigning personnel. The manager also serves in a “quality control” or oversight capacity, especially if the staff member is conducting original research and submitting research papers.

As a program/project manager there is a singular focus on a stated goal with objectives and tasks. A project has a schedule, requirements and a budget. The size and scope of the project will usually determine the reporting structure with a project manager of a very large or visible effort possibly being supervised at the highest levels.

Having said all that, I can identify a small number of efforts in my NASA tenure that mean the most to me and are generally acknowledged by the broader space community as having had a significant impact on the field. The accumulation of that body of work was what led my professional society, The American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) to elect me to the status of Honorary Fellow. You can read more about this accolade HERE, but it’s worth noting this status has only been accorded to 223 people over the past 80 years, including Wernher von Braun and Orville Wright. (As a reference, the AIAA currently has about 30,000 members.)

This article appeared in the local Elizabethtown newspaper upon my invitation to Join NASA in 1987.

1990-1992 Mars Pathfinder, Concept Creator

1993-1996 Mars Pathfinder, Project Manager

I was hired into NASA Ames (one of the 10 Centers managed by NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C.) in late 1987. The Agency was reeling from the loss of the shuttle Challenger and a new President George H. W. Bush was elected. The Center was experiencing a “double hump” personnel problem: a large number of “fresh-out” had been hired and an equally substantial group of employees were close to retirement. There were very few experienced, mid-career staff and a drought of new space projects on which to work. I was 38 when I was hired and fit that most desirable demographic. My supervisor, the late Joel Sperans who was Chief of the Space Projects Division, was quite candid. Ames needed some new space work and he wanted me to be the “rain maker”.

As I reviewed the strategic landscape a new opportunity appeared: Bush 41 announced the Space Exploration Initiative (SEI) in 1989, and the Centers began a rush of activity to respond. Ames, which had been a home for the low-cost Pioneer planetary missions for years was asked to think about some type of project that might help the “back to the Moon – on to Mars” goal of SEI.

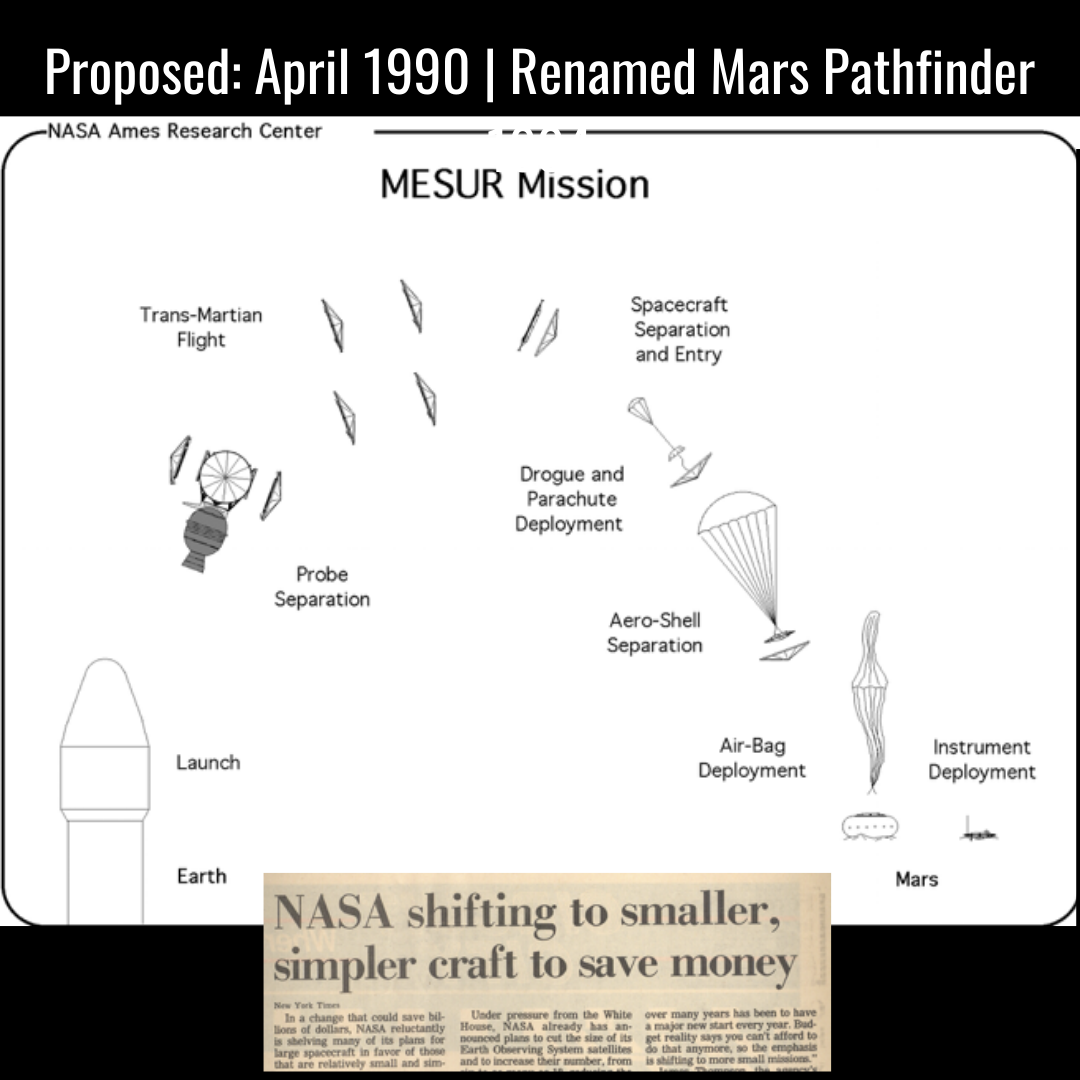

What happened next has been well-documented in my award-winning book “Exploring Mars: Chronicles from a Decade of Discovery”. I put together a study team and in April 1990 unveiled the mission that became Mars Pathfinder. The design of the project with its smaller launch vehicle, cruise-stage, direct atmospheric entry and iconic air bag landing was successfully executed and became the prototype for the Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit and Opportunity.

While the Pathfinder project was ultimately assigned to JPL for implementation, Ames retained the task of working on the atmospheric entry, descent and landing challenges, for which I served as the project manager. Pathfinder launched in 1996.

Changing NASA’s Missions

Top: The original wind tunnel model | Bottom: Pathfinder Lander with airbags

1995-1999 Lunar Prospector Mission, NASA Manager

Almost at the same time as Bush’s SEI announcement, a new program (a sequence of projects) was created by NASA Hqs. This was the Discovery Program of low-cost planetary missions selected through a competitive process. The Program was formalized by a budget line approved by Congress in 1994. During this period of time (1989-1994) word came down that Ames would no longer be assigned any space projects by NASA HQ.

I questioned the head of space science missions at NASA HQs, Wes Huntress, about this policy. What, I said, if Ames were to win a mission through an open competition such as the Discovery Program? Wes’ response was Well, of course, if you win it you can own it and fly it.

As soon as the rules for the Discovery program proposals were released, I began scouting for mission ideas. One of those appeared at our neighbor institution, Lockheed Sunnyvale (before the merger with Martin-Marietta). A scientist had an idea for a very low-cost lunar mission that would fill in gaps of knowledge dating back to the Apollo era. The mission, eventually called Lunar Prospector, had been studied for a number of years and appeared relatively mature. It was one of several we submitted from Ames in that first round of competitive Discovery projects – and to our great delight a winner! Ames remained in the planetary science program.

We successfully delivered a mission to the Moon (with launch vehicle, spacecraft and instruments) for the absurdly low cost of $63M. More detailed descriptions of the mission, its development, and our results can be found via Papers and Publications, numbers 37-42, here.

1998-1999 NASA Astrobiology Institute (NAI), Founding Director

In 1995, then NASA Administrator Dan Goldin began a series of reviews of the NASA Centers, seeking ultimately to economize by perhaps closing one or more institutions. At Ames, we realized that as a research Center, we had less visibility and “clout” than the much larger entities (such as JPL and Goddard Space Flight Center) which could build whole missions in-house. Our salvation came by rallying the science community around the unique combination of life science, earth science, and space science research that Ames housed. We dubbed this interdisciplinary effort “Astrobiology” – the search for life in the Universe. This term is now enshrined various places including the National Academy of Sciences Committee on Astrobiology and Planetary Science (CAPS).

Once Goldin was on board with the concept, he summoned me one day while he was visiting Ames and declared “I want you to create an institute around this science but I’m not going to give you a nickel for bricks and mortar.” Then added, “Oh, and by the way, after you get all this set up and working, I want you to recruit a “King Kong biologist” to put the NAI on the scientific map.

Along with others, I had the challenge to not only create NASA’s first virtual institute, but the first institute devoted to this new scientific area. I set about creating the template for a virtual institute that dealt with a multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary field. It was quite a challenge. It required a great deal of working back and forth across lines of Space Science and Biological Science, and asking scientists to learn the language of the other discipline. At the time—of course, DNA [deoxyribonucleic acid] had been known for a long time—but the field of genomics and understanding of origins of life, and what are called extremophiles—was just emerging, and we wanted to take advantage of it.

The second part of the directive from Goldin also required some creativity. It so happened that there was a visiting scholar at Stanford University (not far from Ames), who happened to be a Nobel Prize winner in physiology and medicine, named Baruch “Barry” Blumberg. He turned out to be a guy who was very curious about this whole field of origins of life and life elsewhere. The Ames Center Director at the time, named Henry McDonald, and I went over to Stanford to visit Barry and we pitched him the idea of taking this on. It worked! Except for John C. Mather, the gentleman from Goddard who won the Nobel Prize for the Cosmic Background Explorer mission, I think this was the very first Nobel Prize winner who had ever actually been employed by NASA. So this was a big deal, and it helped put astrobiology on the map, and the Institute, of course. He became an exceptional advocate for the program through the years and I am proud to have launched the NAI and recruited Barry.

Not long ago, the NAI celebrated its 20th anniversary and I am very proud of what we accomplished. (You can read the talk I gave at the event here.) Hundreds of researchers across many institutions have participated and contributed. The term astrobiology appears routinely in the scientific literature and is a mainstay in instrument selection for scientific missions. Some universities now offer a Ph.D in astrobiology. I am also proud of the virtual institute model I created which has now been copied three more times by NASA, in an aeronautics institute, a Lunar science institute and a Solar System Exploration institute. Seems a good idea will have “legs”.

With 12 Astrobiology member institutions across the United States, we were excited to welcome Spain as the first International affiliate.

Pictured: Spanish Prime Minister José María Aznar and I shake hands, with Barry Blumberg seen between us. In the extreme left background you can glimpse Murray Gell-Mann, another Nobel Prize winner.

2000-2001 First Mars Program Director (aka “Mars Czar”)

Of all the accomplishments during my time with NASA, being the very first Mars Program Director, or “Mars Czar” as I was dubbed by the media, was the most visible and arguably of the most impact world-wide.

Here I would like to invoke the privilege of my multimedia autobiography and encourage you to watch my presentation on Mars, “Exploring Mars with Robots and Humans” that goes into the creation and achievements of the Mars program in detail, with many excellent visuals. The connection to music will become obvious immediately since this lecture was recorded aboard the Delbert McClinton cruise!

For greater detail, my story of how all this came about is well documented in my award-winning book, “Exploring Mars: Chronicles from a Decade of Discovery”.

Additionally, I’ve often been asked to present the details regarding the creation of the Mars program as lecture. You can view it below here, or get your own DVD copy of the presentation here.

One important coda is that all the “follow-the-water” theme of my tenure has now resulted in the scientific, programmatic and technological basis for the long-sought Mars Sample Return mission.

2003 - The Columbia Shuttle Accident and Investigation Board:

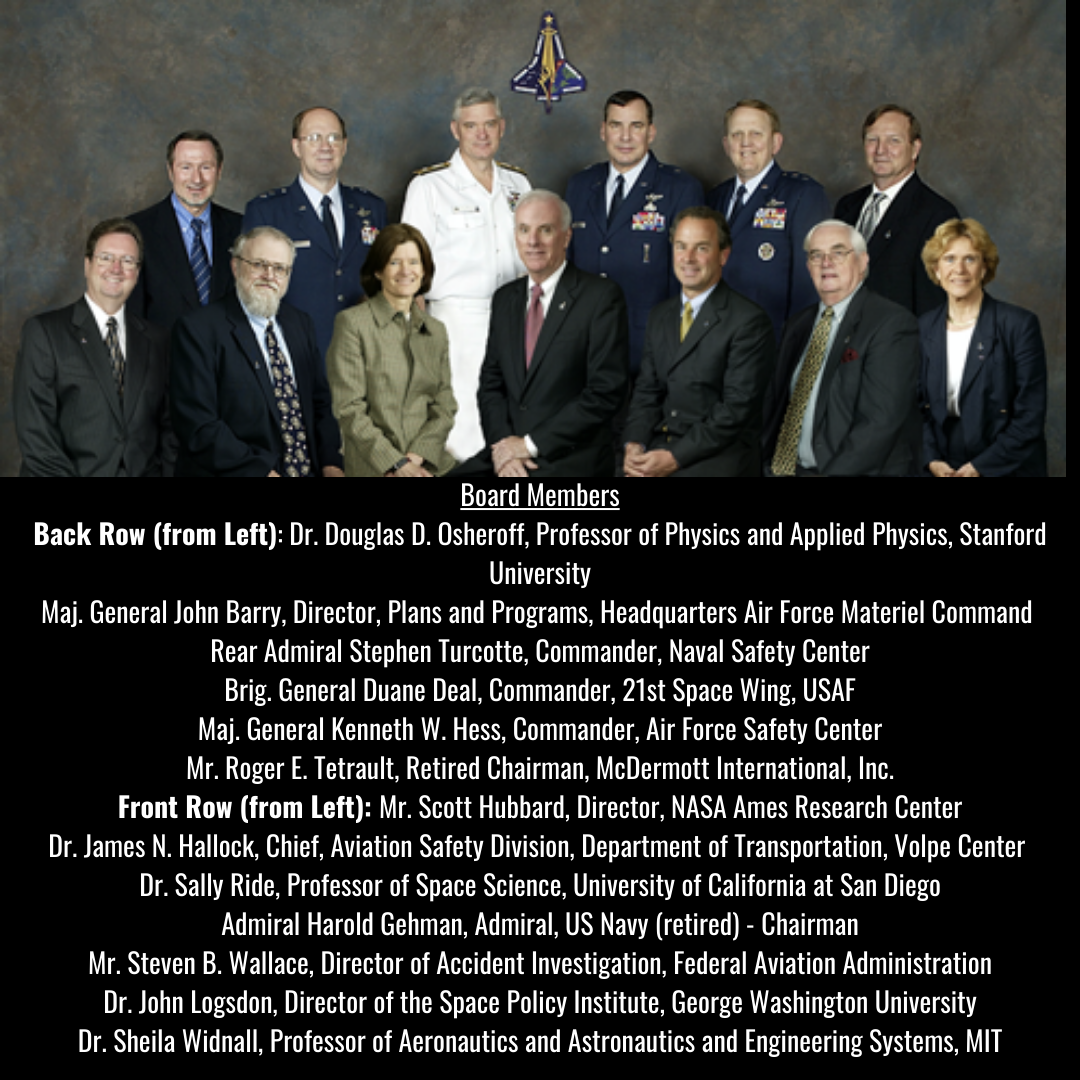

In 2002 I was promoted to the role of Center Director at Ames, but just about 5 months after I was named to the position, on February 1, 2003, the Columbia shuttle was destroyed as it re-entered the atmosphere. I was asked by then Administrator Sean O’Keefe (who had just appointed me as Center Director), to serve on the Columbia Accident Investigation Board (CAIB). I ended up serving essentially full time from February 1 until September in what was the most difficult duty of my time at NASA.

An overview of the events that transpired on that day and the subsequent investigation, are captured in an excellent article by William Langewiesche from the November 2003 Atlantic.

You can read the full CAIB report, as presented to Congress and submitted to the Library of congress here.

In an effort to share what we learned, I often present a lecture on the investigation to CEOs and senior managers of other high-risk businesses. (You can watch an overview of the talk here or review a PDF outline of my presentation here.)

One of the points I make is that I ended up being the Columbia version of Dr. Richard Feynman who, in 1986, used a glass of ice water, clamps and a small O-ring to show the cause of the Challenger accident to Congress. It took me months, a large team of engineers and technicians plus a modified facility in the outback of San Antonio, Texas to show how falling foam destroyed the Columbia orbiter. Achieving that objective required overcoming the objections of NASA itself, which at times seemed not to want a definitive demonstration.

It is my hope that my experiences will be an example of management successes and failures in a high consequence environment.

2002-2006 Director, Ames Research Center

Following my 7-months on the CAIB, working nearly seven days a week throughout, I was relieved and enthusiastic to return to my role as Director at Ames. My philosophy in the role, and what I proposed to O’Keefe when he was considering me, would move Ames ever so slightly from “University of Ames” toward “Ames, Incorporated.” What I meant by that was that I would try to keep the culture of research but be sure that we had things operating on a fiscally sound approach, and would emphasize outreach to the rest of Silicon Valley.

I attempted to address what the researchers would complain about continuously, from lower-level employees to division chiefs. Their constant consternation was that some combination of procurement personnel and legal was keeping them from doing innovative stuff that they wanted to do.

Of course, I had to look at it from the perspective of making sure that the Center did not get involved in anything that was going to end up as an embarrassment in the San Francisco Chronicle or the New York Times, that nobody was going to go to jail, and that the fiscal responsibility was in place.

Within that framework, though, what I think had some success at, was to change the relationships, the respect, and the attitudes to realize that this was a research center and that we had to produce top level research, leading-edge research products, in order to have our standing in the Agency and continue into the future. That objective included government public-private partnerships, and I needed the help of procurement personnel and legal to make that happen.

During my tenure as Center Director, there were two management/executive leadership issues that caused a great deal of discussion, concern, and effort at all of the Centers: Full Cost Accounting and the role of the Center Director. They were complicated issues, rooted deeply in the history of the organization. I won’t go into all of it here, but, if you’re inclined, you can read about it more completely on page 21 of the third Oral History session I did with NASA.

In that role, through the years, I developed my skills as a tightrope walker rather proficiently, treading carefully between the permanent civil service and political appointees. The beauty of the civil service is that it takes its marching orders not only from the political appointees that come and go, but (as in the case of Ames) focuses on the research and long-term commitments of a scientific nature. After all, you don’t explore Mars in one presidential cycle! But at the same time, in order to sell programs, you often had to talk to these political appointees about what could be done during their four years or their President’s four years. It really results in a kind of often strange psychology or sociology. You’re trying to be faithful to, let’s say, a decadal survey, where the scientists of the world get together and say, “This is what we want to do over the next 10 years,” versus a rapid changing political environment where people come and go and are often driven not by some long term vision, but by the 24-hour news cycle or whatever is happening on Capitol Hill. It’s quite a balancing act.

There are two examples of public-private relationships that I regard as a significant legacy.

The first achievement was to substantially reinvigorate Ames’ leadership role as NASA’s principal center for supercomputing. Supercomputers first emerged at Ames for aeronautics in the critical discipline of Computational Fluid Dynamics and eventually became vital for every field from astrophysics to Earth science. But, by my tenure as Center Director, Ames had almost fallen off the top 500 supercomputing facilities world-wide list.

In the highly competitive world of supercomputing, there is an annual “bake-off” where supercomputing firms from every nation would compete to demonstrate the world’s fastest computer. In Silicon Valley, both Intel and Silicon Graphics (SGI) were determined to recapture the title from Japan. We at Ames had the floor space, the necessary power, the personnel, and, most importantly, the applications for such a capability. In a remarkable effort after I was able to convince NASA HQS that this was a necessary tool, the engineers and scientists at Intel, SGI, and Ames created the world’s fastest computer in our NASA building in just 120 days. The mantra was “a miracle a day” was all we ask.

The device has since been upgraded many times over by my successors, but that event in May 2004 put Ames back on the supercomputer map.

The second accomplishment was a deal with Google announced September 30, 2005 at a national press conference to pursue R&D collaborations with NASA ARC and plan to build one million square feet of new facilities in our NASA Research Park. In addition we would collaborate on large-scale data management, massively distributed computing, Bio-Info-Nano convergence and R&D activities to encourage the entrepreneurial space industry.

Signing the agreement with Eric Schmidt, CEO of Google, in 2005.

In 2005, a new Administrator, Mike Griffin, took over at NASA. Bright, opinionated and a former participant in the Star Wars program of the Reagan era, Mike was certain that what NASA needed was a complete makeover, with nearly all new staff of his choosing. I knew Mike from his earlier DoD days and initially had a good relationship. But by late 2005, Griffin had replaced nearly all the Center Directors and I was hearing that his old friend Brig. Gen. Pete Worden needed a job. Pete apparently indicated that he would really like to be at Ames. Sure enough, I received a call from Griffin very late in 2005 saying he wanted to “make a change” and offered me several options as another assignment. Thus it was in early 2006 I made the decision to leave NASA.

Rather than put up an unseemly public fight about all that was transpiring, I felt I had accomplished a great deal and that the time was right for me to focus on something I really enjoyed, which was astrobiology.

In public, I simply stated that Mike “wanted his own team”. And, shortly after I took on a role at the SETI Institute and Stanford. Pete Worden was named Ames Center Director.

This is my official NASA Ames Center Director oil portrait. It hangs on the second floor of the main administration building at NASA Ames.

The background is meant to suggest all my accomplishments with NASA: Mars Program, Lunar Prospector, Supercomputing, the agreement with Google, Columbia Accident Investigation Board.

Portrait Artist: Robert Seman - 2008